Tony Flannery – who asks in his latest book: ‘What is the point of the Creeds?’

By far the worst thing ever to happen to the Christian Creeds of the early centuries was that they became tools of persecution by hunters of Christian heretics in the Middle Ages. (c. 476 CE – c. 1453)

The second-worst thing that happened to them was their use by the compilers of Catechisms – for the persecution of many generations of Christian children who could be beaten in school for failing to remember what the Catechism said.

With one self-defeating arm of the bureaucracy of the Catholic Church still in pursuit of heretics today, it is no wonder that cancelled Catholic priest Tony Flannery should ask in his latest book ‘What is the point of the Creeds?’

The shortest answer to this question goes as follows:

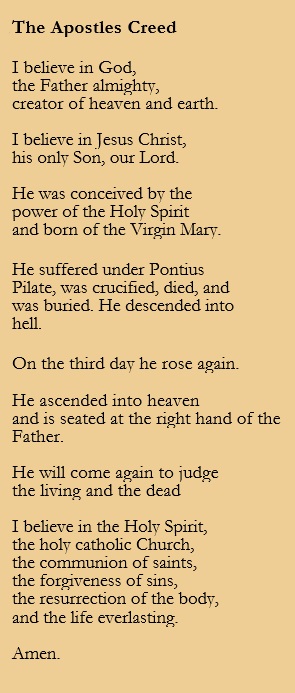

First, the Apostles Creed is a summary of the faith the led the earliest church through its worst persecutions. It was a passport through persecution, NOT a licence for persecution – and should never have been used for that purpose.

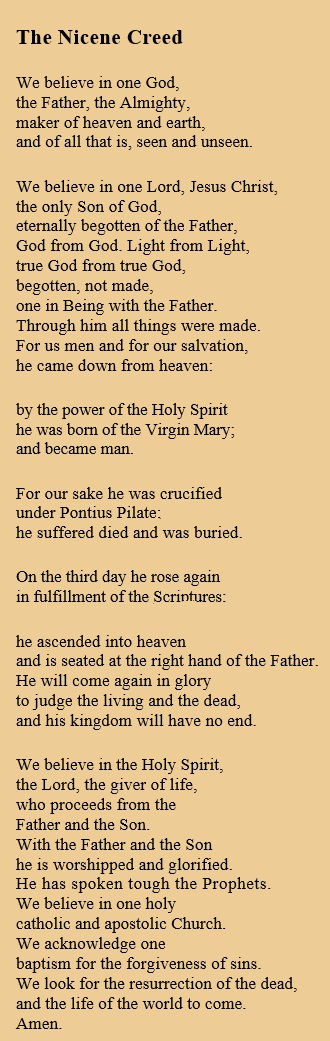

Second, the Nicene Creed is a mere ‘tweaking’ of the Apostles Creed, to insist upon the equality of all three persons of the Trinity – Father, Son and Holy Spirit. It should never have been used as a tool of religious oppression either.

The ‘Credo’ of Jesus of Nazareth

The English word ‘Creed’ derives from the Latin word ‘Credo’ which means ‘I believe’. Every firm believer is in need of a summary of what they believe – and Jesus’ own people, the Jews had that. Called the ‘Shema‘ (the Hebrew word for ‘Listen’ or ‘Hear’) it was recalled by Jesus when he was asked, in Mark’s Gospel, what was the greatest of the commandments.

He replied as follows:

‘This is the first: Listen, Israel, the Lord our God is the one, only Lord, and you must love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your mind and with all your strength. The second is this: You must love your neighbour as yourself. There is no commandment greater than these.’ (Mark 12: 29-31)

This was a direct quotation from one of the oldest of the Hebrew scriptures, or ‘Old Testament’, the Book of Deuteronomy. ‘“Hear O Israel: Yahweh our God is the one, the only Yahweh. You must love Yahweh your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your strength.” (Deut 6: 4,5)

Because the Apostles Creed affirms Jesus as ‘Son of God’ it follows that what Jesus believed is also binding for Christians, so we believe ourselves also bound by the ‘Shema’ as the basis of all other laws, including the Ten Commandments given to Moses.

As explained by Luke Timothy Johnson in ‘The Creed’, the Apostles Creed grew naturally out of the Shema – to explain to Jews and Gentiles why Jesus’s story was central to Christian belief.

Jesus’s Crucifixion was a Beginning, not an End

The earliest Christians believed firmly in Jesus’s survival of crucifixion. What is impossible for many who are attracted to Jesus’s teachings today – the belief that he had been somehow raised from the death proscribed by a Roman governor of Palestine, in about 30 CE — was the firm belief of those who compiled the four Gospels and the Creed.

It is obvious also why that belief was affirmed in the Creed. It reassured the Christian believer that his or her own life would endure beyond physical death – as a follower of this man who had not been simply obliterated by the worst persecution that the greatest empire of the time could devise.

It is the most grotesque irony of the history of Christianity that the Creed should itself in later centuries have become an instrument of persecution. To call Jesus ‘Lord’ was, for the first Christians, to deny supreme authority to Caesar – and therefore to endanger oneself, as Jesus himself had done by criticising the religious elite of his own time.

On the third day he rose again.

This insistence on the truth of the Resurrection of Jesus is the central and pivotal statement in the Creed – explaining everything that comes before that in the Creed, and everything that followed. For the purpose of the Creed was to assure the believer that in following Jesus, as a mere human, the same victory over death could be achieved. The power claimed by Rome, or any other authority, was thereby ‘relativised’ – reduced to mere appearances and ‘passing away’ – temporary.

That Jesus was human also – as vulnerable to suffering and death as the rest of us – was therefore also to be believed. For otherwise how could survival of death be possible for merely human believers in Jesus?

But Jesus was also ‘Son of God’ and himself divine. So therefore, somehow, he had been ‘conceived’ by – or ‘brought into being by’ – the Holy Spirit of God.

How are we to understand today the insistence upon the ‘virginity’ of Mary, the mother of Jesus? Some scripture scholars tell us that the original meaning of the word did not originally imply that Jesus’s conception happened without sexual intercourse, but that probably cannot be proven, What is certain is that the process by which Jesus was ‘conceived’ or ‘begotten’ by God was for early Christians a secondary matter – dependent upon the conviction that through Jesus we come to know God – and to know that God is love.

The Creed Summarises the Gospels

Because the Creed was in later centuries used to justify the persecution of Christian ‘rebels’ or ‘heretics’, it is sometimes alleged that it was the product of the Constantinian Roman Empire – and therefore NOT what Christians originally believed. This can be disproven simply by comparing it with what is asserted in the four Gospels.

Because the Creed was in later centuries used to justify the persecution of Christian ‘rebels’ or ‘heretics’, it is sometimes alleged that it was the product of the Constantinian Roman Empire – and therefore NOT what Christians originally believed. This can be disproven simply by comparing it with what is asserted in the four Gospels.

To take just the Gospel of Matthew to start with, it is clear that the belief that God is a ‘Trinity’ of three persons was central to the early church. Completed probably by as early as 100 CE Matthew’s Gospel gives us in Chapter 28 Jesus’s final instruction to his followers, AFTER the crucifixion:

Go, therefore, make disciples of all nations; baptise them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. (Matt 28: 19)

In that one Gospel, therefore, completed centuries before Constantine, we find the central beliefs of the Creed – that Jesus had survived crucifixion and taught that God was a Trinity.

The Nicene Creed affirms the Equality of the Trinity

Although the Nicene Creed – to the right – did emerge in the wake of Constantine’s decision to approve Christian belief it is also clearly a mirror of the earlier wording. What is distinctive about it is simply its insistence upon Jesus as an equal member of the Trinity – something questioned by Arianism, a ‘heresy’ of the time that made Jesus clearly inferior in status to the Father.

Can Unarmed Love Conquer Death?

Think about it just for ten seconds. Other than the complete faith of the founders of the Christian tradition that Jesus had risen, what else can explain why there ever was a Christian tradition?

That faith has proved far stronger than the Roman imperial conviction that crucifixion would do what the Romans were certain it would do – scrub anyone who suffered it completely from historical memory.

All merely human empires are built on a premise of permanence via the shaming of others, and almost everyone knows now what a ghastly and doomed premise that is.

The Creed simply means that it is unarmed truth in the face of armed power that drives history forward. Through their courage and their vulnerability, it is the speakers of unarmed truth to power who are best remembered and best loved.

Because, somehow, truth-tellers, whistleblowers, are definitely not ever, in any circumstances – truly alone.

A very historical, comprehensive and informative explanation for why the Catholic Church has a Creed and invites the congregation at Mass every Sunday to recite it.