Sunday, March 22, 2020

I am not alone in my tiredness or sickness or fears, but at one with millions of others from many centuries, and it is all part of life. —Etty Hillesum

The “cross,” rightly understood, always reveals various kinds of resurrection. It’s as if God were holding up the crucifixion as a cosmic object lesson, saying: “I know this is what you’re experiencing. Don’t run from it. Learn from it, as I did. Hang there for a while, as I did. It will be your teacher. Rather than losing life, you will be gaining a larger life. It is the way through.” As impossible as that might feel right now, I absolutely believe that it’s true.

When we carry our own suffering in solidarity with humanity’s one universal longing for deep union, it helps keep us from self-pity or self-preoccupation. We know that we are all in this together. It is just as hard for everybody else, and our healing is bound up in each other’s. Almost all people are carrying a great and secret hurt, even when they don’t know it. This realization softens the space around our overly-defended hearts. It makes it hard to be cruel to anyone. It somehow makes us one—in a way that easy comfort and entertainment never can.

I believe—if I am to believe Jesus—that God is suffering love. If we are created in God’s image, and if there is so much suffering in the world, then God must also be suffering. How else can we understand the revelation of the cross? Why else would the central Christian logo be a naked, bleeding, suffering divine-human being? The image of Jesus on the cross somehow communicates God’s solidarity with the willing soul. A Crucified God is the dramatic symbol of the one suffering that God fully enters into with us—much more than just for us, as many Christians were trained to think.

If suffering, even unjust suffering (and all suffering is unjust on some level), is part of one Great Mystery, then I am willing to carry my little portion. Etty Hillesum (1914–1943), a young, Dutch, Jewish woman who died in Auschwitz, truly believed her suffering was also the suffering of God. She even expressed a deep desire to help God carry some of it. How many people do you know who feel sorry for God and want to “help” God within us? She has a stronger sense of the Divine Indwelling within her than most Christians I have ever met:

And that is all we can manage these days and also all that really matters: that we safeguard that little piece of You, God, in ourselves. And perhaps in others as well. Alas, there doesn’t seem to be much You Yourself can do about our circumstances, about our lives. Neither do I hold You responsible. You cannot help us, but we must help You and defend Your dwelling place inside us to the last.

Such freedom and generosity of spirit are almost unimaginable to me. What creates such altruistic and loving people? Perhaps this season of disruption will offer us some clues. I certainly hope so.

[1] Etty Hillesum, An Interrupted Life and Letters from Westerbork (Henry Holt and Company: 1996), 157.[2] Ibid., 178.

Adapted from Richard Rohr, The Universal Christ: How a Forgotten Reality Can Change Everything We See, Hope For, and Believe (Convergent: 2019), 160, 161–162; and

A Spring Within Us: A Book of Daily Meditations (CAC Publishing: 2016), 122.

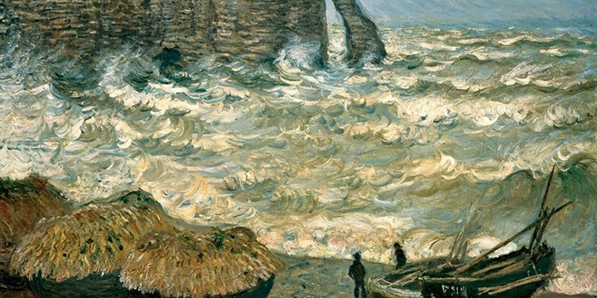

Image credit: Agitated Sea at Étretat, Claude Monet, 1883, Museum of Fine Arts, Lyon, France.

© 2020 | Center for Action and Contemplation

1823 Five Points Road SW

Albuquerque, New Mexico 87105

USA

0 Comments