The Three Marys at the Empty Tomb – Peter Cornelius c. 1820

For the earliest Christians, Jesus’s Resurrection had set them free from the worst kind of fear – that the judgement of Rome was God’s judgement also. Without an army, Jesus had defeated the world’s greatest power, simply by speaking the truth. The still living Jesus, their brother and Lord, was now judge of the living as well as the dead. In their own minds and hearts, whatever others might think, they were beloved children of the only God who mattered.

If crucifixion could not disgrace or kill Jesus it could not disgrace or kill those who believed that Jesus was indeed the way, the truth and the life.

And so St Paul could write : “Now this Lord is the Spirit and where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom.” (2 Cor 3: 17)

This was why Jesus was also called ‘Redeemer‘ – liberator – because his forgiveness, experienced before Baptism, had also liberated his earliest followers from the fear that eternal death would follow not only from the mistakes of their own earlier lives but from crucifixion

To ‘redeem‘ was literally to buy the freedom of a Roman slave, so those earliest Christians were truly free in the most important sense. The greatest power that Rome had – the power to both kill and shame by crucifixion – had been set at nought by Jesus.

That cruel Roman world was passing away.

![]()

Two thousand years later a Christian descendant of African slaves in the USA was to write as follows:

“The cross stands at the centre of the Christian faith of African-Americans because Jesus’ suffering was similar to their American experience. Just as Jesus Christ was crucified, so were blacks lynched. In the American experience, the cross is the lynching tree.”

(James H. Cone, The Cross and the Lynching Tree, Orbis Books, 2013)

James Cone was describing the belief that had led Martin Luther King to give his own life for the cause of African American civil equality in the USA, the Civil Rights campaign of 1956-68.

The same belief – that God and history are always on the side of the enslaved and the abused – the rejected ones – continues to make history today.

The paradox is that James Cone’s own ancestors had been enslaved by white Europeans who also thought themselves Christians. Those white Europeans had instead used the Bible to justify their own greed and brutality.

The white American landowners to whom they had sold their slaves had given the same Bible to those slaves in the hope that it would teach them obedience. They had no expectation that something utterly different would happen:

Those slaves now saw in the story of the Israelites in Egypt their own story – and in the crucifixion they saw the lynchings that became all too frequent after the US Civil War defeat of the slave-holding southern states, in the period 1865-1945.

How had it happened that white European slavers – and even kings and popes – had forgotten what St Paul had also written about the Kingdom of God called into being by Jesus long ago: “There can be neither Jew nor Greek, there can be neither slave nor freeman, there can be neither male nor female — for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” (Gal 3: 28)

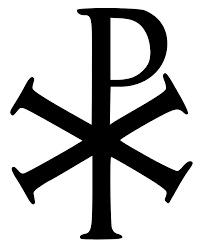

The Chi Rho – early Christian symbol formed by placing the first two letters of the Greek word ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ (Christos) on top of one another. It was adapted to become the battle standard of the armies of the Roman Emperor Constantine 312-337 CE

Emperor Constantine ‘the Great’

The answer lies in an event that happened just three centuries after Jesus’s time on earth: the decision of the Roman Emperor Constantine to claim in 312 CE that the God of Jesus had helped him win power over his rivals, and would help him to further victories if he marched under a Christian symbol of that time – known as the Chi Rho.

Not all Christians were convinced of the truth of Constantine’s claim – for it was also known that Constantine had earlier claimed the support of the pagan God Apollo. However, a majority of the Christian bishops decided that the sufferings of Christians under periodic Roman persecution had finally been rewarded, and did not contest this claim. By the end of that century, 400 CE, Christianity had replaced belief in the ancient Roman and Greek Gods as the official religion of the Roman empire.

This had a profound impact on European Christianity from then on, in three main ways:

- First, as the Christian church was now under the protection of a military Roman upper class, it came itself to be organised in the same way – with Christian clergy organised also as an officer class and social hierarchy throughout western Europe.

- Second, the social importance of Baptism lessened greatly. Originally received by adults converted by the ‘Good News’ of Jesus life, death and resurrection, Baptism became gradually a sacrament received in infancy in Christian families. This strongly contrasted with the rising social prestige of the adult sacrament of ordination – the gateway ‘rite of passage’ to the Christian clergy, the church’s own officer ranks.

- This in turn meant that ‘Redemption’ for most European Christians no longer meant freedom in the present from fear of the judgement of others, but merely a promise of eternal life after death – if one was obedient to the Christian clergy who now formed society’s moral and intellectual elite.

This was Christendom – an era that began in the 300s CE and lasted, as a semi-Christian society, until 1914 CE. Its downfall came when five ‘great’ European imperial powers fought World War I, the most absurd and costly war in history – the Great War of 1914-18 – all claiming that the God of Jesus would help them to victory.

This disaster – its effects still ongoing – has greatly weakened those Christian churches that had supported those imperial powers. It has led many Christians in all traditions to recall that Jesus began his ministry by resisting the temptation to seek any form of political or ecclesiastical power, and that he died holding to that same course. Christendom was obviously not the Kingdom of God, and this is slowly being understood.

James Cone’s statement quoted above helps us greatly both to pinpoint the greatest mistake of European Christian churches in the past and to chart the future.

At the highest level of the church today it is also understood that the importance of Baptism took a negative turn following the Constantinian conversion in the 300s CE:

” Theology and the value of pastoral care in the family seen as domestic Church took a negative turn in the fourth century, when the sacralization of priests and bishops took place, to the detriment of the common priesthood of baptism, which was beginning to lose its value. The more the institutionalization of the Church advanced, the more the nature and charism of the family as a domestic Church diminished.” (Secretary General to the Vatican Synod of Bishops, Bishop Mario Grech, Civilta Cattolica, 16th October 2020.)

And that is why defending the importance of Baptism and raising its status in the church needs to be a priority for all Irish Catholics today – especially because of the continuing power of clericalism – a mistaken exaggeration of the importance of ordination. Clericalism pays only lip service to Baptism. In particular, Irish clericalism still denies the baptised people of God the ordinary necessity of frequent dialogue. This in turn means that clergy are too often unable to help lay people to develop a mature Christian faith that is free of the need of clerical approval and oversight.

Yet,in 2020, as Catholic clerical morale reaches its lowest ever ebb in Ireland, many Irish Catholic lay people are discovering that the Holy Spirit, the counsellor promised by Jesus, is always at their elbow, reminding them that with the fullest understanding of the Apostles Creed comes a freedom greater than they have ever known. It does not matter that due to its mistaken alignment with wealth and power in the past, Catholicism is written off by today’s fashionable opinion-makers.

Those same opinion-makers existed in Jesus’s time – he called them ‘the world’. Knowing that world was passing away he left to all Christians a far greater faith in the living presence of the Holy Spirit and in the better world to come.

In the end all human judgement and social and spiritual pretence is set at nought by the Cross. It is our pride, our mistaken pursuit of superiority, that leads to snobbery, inequality, clericalism and injustice in all eras.

Prayer – especially reflective prayer on the Apostles Creed – will remind us that it is the Trinity – Father, Son and Holy Spirit – who are the true Lords of Time. As ever we are all equally and infinitely loved, and need to believe this firmly to become a true Christian community – and heralds of the world to come.

A great article, putting the current and rapidly declining situation of the Catholic Church in Ireland into its historical context. The final prayer is a very suitable and deeply biblical summation of the whole article.

The Church in a multiplicity of its documents repeatedly urges the meaningful involvement of the laity in the evangelical mission of Church together with the duty of the laity to participate in such. A Catholic association pursuing this objective has to explain to the laity just what this duty entails. It is not enough to respond to an article such as the present one by saying that the article demonstrates the reason for the state of the Church in a particular country at any one time.

A recent article on this website addressed the debacle that is the celebration of First Holy Communion in many parishes nationwide. This current article equally focusses on the underwhelming efforts that often obtain in the promotion of catechesis on the essential nature of Baptism.

This article also speaks wisely of “DIALOGUE” between laity and the ordained priesthood. One of the requirements of dialogue is that the parties involved recognise the essence, dignity, proper function and levels of authority of the other.

If it is claimed that the problems cited above concerning First Holy Communion and Baptism can be solved by handing greater amounts of authority to the laity, then this assertion has to be supported by credible arguments of a theological type and by evidence.

Teachers who have experienced or led curriculum development projects know the vital importance of teacher/student interaction. This one feature moderates dispositions to a degree that can amplify or frustrate the impact of the most credible forms of teaching approaches. It is the same in the case of the mission of the Church – holiness is the key issue for both priestly and lay endeavour. The best arguments will spring from that. But holiness is an acquired characteristic and one can’t postpone priest-lay initiatives until everyone is “perfect.”

As regards evidence, “one swallow never makes a summer.” One can understand why it is difficult to produce robust evidence.

But!!!

If a Catholic association has a special relationship with a particular association of priests, and both speak a lot of the same language, why don’t both undertake a priest-lay tightly defined project exploring a remedy for either of the two problems surrounding First Holy Communion or Baptism. Efforts at lighting the candle are by definition more exciting than ….

That last is a helpful suggestion, Neil. Based so far away from Dublin, in a region where the ACP is not to my knowledge ‘thick on the ground’ I will flag that for our more likely members. There is exactly the need you summarise for collaboration on that particular issue – I cannot see how the problem can otherwise be resolved.

Re ‘levels of authority’ and ‘holiness’, those obviously belong to quite separate categories, and frank discussion of both in the wake of e.g. the Ryan report of 2009 has too long been deferred. I cannot see how ‘holiness’ can be understood as something entirely different from, or ever lacking in, integrity, yet the lack of integrity so visible in the deference of too many lay civil servants in the ROI department of education in the exercise of responsibility for the care and safety of children in clerically managed institutions in the last century has not, as far as I know, yet led to a discussion of the obvious danger that deference to clergy will be seen as an obvious corollary of ‘levels of authority’ as understood, apparently, by e.g. Pius X. (priests lead, lay people follow).

This obviously impinges on our understanding of the freedom and obligations of individual conscience when it comes to considering holiness also – in its relation to ‘levels of authority’ and the role of lay people in the church. I have not felt in a long time that our clerical body as a whole actively encourages candour in all of this, and candour too is a virtue. My guess is that the understanding of holiness that most practising lay Catholics still have inclines them to be deferential if they also wish to be considered holy – and that our clergy are mostly not yet ready to disagree. I cannot see how we can be ready for evangelisation until this is ‘sorted’, for that understanding of ‘holiness’ is surely seriously wanting in light of decades of recent experience, and even of the need for trust in the NBSCCC – and is therefore unlikely to recommend itself to so many in Ireland who have become alienated and even cynical, and derisive of ‘holiness’, for that very reason.

Neil, while bishops and parish priests can say “I am solely responsible for the total running of this parish/diocese” and include aspects in that responsibility for which they have little or no competence, and operate within a system which lays no duty or legal requirement on them to have or to consult a parish/diocesan council, dialogue will vary greatly between parishes and dioceses. In that situation, it is at the arbitrary will of priest or bishop concerned.

That is why I think a fundamental change in the management structure of the Catholic Church, from Vatican to parish, is urgently required. It will likely require the ruling of a Third Vatican Council to bring it about.

As Frederick Douglass said “Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.” The problem is that very few lay Catholics are currently demanding it. They don’t see the point. Many couldn’t care less anyway as their involvement and vision are limited, partly because of long standing clericalism, to observing the obligation of attending Sunday Mass. The more unaccountable the power the less likely it is to be given up and more likely the powerless are to walk away. That is certainly happening within the Catholic Church at this time

A very accurate comment, Aidan, which captures a number of the key issues influencing the current decline of the institutional church – in this country, in particular. So many lay people are indifferent to the church hanging on to the ‘unaccountable power’ you speak of because it has no impact on their lives. The cohort that cares could be described as a combination of many who get on with their faith lives, meeting their obligations, while ignoring the negative and demoralising impact of clericalism which has brought us to where we are. Another group are those who care and work to try to bring about change – for example the ACI and other reform focused organisations – but from experience [in the case of the ACI anyway] it is proving to be a very difficult and painfully slow path. What will it take to accelerate the process to the point where our episcopal leaders acknowledge the current reality which is surely the starting point for any reform and renewal effort.

Two considerations

First an instance of a small group of competent, trustworthy parishioners attending The Sacrifice of the Mass every week. They decide to organise the renovation of the local rural parish church and to work independently of the normal parish procedures. They hold a meeting and manage to collect sufficient finance for a professional estimation of the costs associated with an appropriate comprehensive renovation. The projected cost comes to a six figure sum. They then investigate methods of collection. The presumption regarding the role of the parish priest (decent, humble, and reasonable) was unclear.

On foot of investigation the group decide that the most tax efficient way to collect the money is to put their finances under the ambit of those of the parish and they hold two parish meetings (30-35 enthusiastic people) to disseminate this information. But the situation becomes unclear and everything stalls.

Canon Law requires that all parish finances be the responsibility of the PP. Should the group mentioned here submit the financial responsibility associated with the renovation project and the conduct of the renovation itself to the jurisdiction of the PP? Are they duty bound to do so? What is there to prevent a rival group with the finances necessary to undertake the renovation of the church or even to build a new church in another part of the parish?

Suppose that somebody issues a legal action for damages arising during the conduct of the renovation project. To whom is the solicitor’s letter sent? What considerations of indemnity arise?

In general does a transfer of authority from clergy to laity in some spheres require a change in Canon Law? And to what effect?

Second consideration

To what extent would a transfer of authority from clergy to laity have improved the evangelisation inherent in the ministry of The Cure of Ars?

There is no rhetorical intent in the questions posed above. They are asked with a view to understanding the policy of the ACI in relation to the empowerment of the laity.

When people love authentically they evangelise without any transfer of authority. Their authority is not ‘over’ people but the evangelical authority awarded to those in the early church who simply loved better. If The Cure of Ars was helpful in leading people to do that he was markedly more successful than the many priests today who are extremely sensitive about their canonical and financial authority but totally oblivious of what the Good News might be.

The examples you give have markedly to do with money and bricks – and remind me how dynamic the early church was without either and how inert it has become with a superfluity of both. The building program you envisage seems remarkably unnecessary also since empty church space is expanding and the younger generations for whom the Gospel could be salvational will never learn that from clergy obsessed with their canonical authority and the security of parish finances.

It wasn’t until the church became secure in the fourth century that a separate full-time clergy emerged, dependent for financial support upon the unordained. Significantly that was also when they began lording it over the unordained and the family began to lose its authority in relation to child faith formation.

And levels of authority and holiness became separate categories, and integrity became something else. And soon there was the council of Elvira and the first documentation of clerical sexual abuse of children. Do you notice the coincidence of a cultic priesthood and that phenomenon?

How can anyone suppose that following the McCarrick report that notion of ascending levels of authority can mean anything other than ascending levels of both unaccountability and scandal? There is no Christian integrity – or holiness – without humility – and if Jesus ever fussed about levels of authority, please cite the occasions.

I think, however, that you have fully explained why he handed financial management to someone else, had nowhere to lay his head and uttered never a word about canon law. His narrow door was the dangerous integrity – holiness – he himself exemplified and he left no blueprint for a pyramidal church. All pyramidal institutions award dignity unequally – the reason they corrupt. They therefore pose exactly the challenge to integrity that our elevated levels of authority catastrophically failed.

We have never had a more effective lesson on why, for authority, we must turn directly to the Lord of the Gospel, and follow Him

As I said there was nothing rhetorical in my last submission. It was not a contest.

But I am none the wiser now regarding the questions I put.

In the case of the renovation of a Church envisaged and initiated by a group of laity and supported by a larger group and indeed by a priest – your decision would be not to undertake it at all because of a possible lack of Catholics to use it. But the same question would still arise in the event of the Church building being absolutely necessary.

The central issue is one of faith, hope and charity. The congregation known as the Institute of Christ Sovereign Priest has in recent years purchased a disused Jesuit Church in Limerick and has also purchased a Presbyterian church in Belfast. Their first house in Ireland was in a rural dwelling.

Coincidently the Cure of Ars did extend the size of the church in Ars significantly. I’ve seen it. He had to manage a lot of money. More to the point of my submission he also engaged the service of the laity in different projects he launched. My question pertained to the possibility of ascertaining how his type of lay-priest cooperation would accord with that envisaged by the ACI. He is, for obvious reasons the patron saint of priests. Could he be the patron saint of lay-priest cooperation?

Christ did transfer financial management of his affairs to lay person. The Vatican has done the same in recent years. It is fair to say that in both instances the outcomes were not always optimal. Irrespective of who administers the money, it can’t be assumed that financial probity will always be the order of the day without some instance of authority.

The issue of transfer of something from clergy to laity is recurrent in a major way in this website. Is it a transfer of authority, or control, or management, or influence? Can you be clearer on that issue? And are you saying that Canon Law can be dispensed with?

The following was not your intention. But if a group of individuals, in this case priests, are told that they are of disreputable regard, it is unlikely they will be enthused into further “dialogue” as understood in the article above.

“Is it a transfer of authority, or control, or management, or influence?”

My guess is that just as the authority of the priest re evangelisation will evaporate if he does not expect lay people ever to open their mouths in that cause, so will trust in clergy alone to manage money if they do not share that role also and understand the importance of transparency and acceptance of the role and advice of lay people, both in deciding what money might be needed for, and how misuse of it could be prevented.

Am I reading you wrong in supposing that you think that authority cannot be shared – that if lay people have any of it, clergy must thereby be deprived of what they have allowed lay people to exercise? This US dialogue re financial probity surely proves otherwise:

https://www.ncronline.org/news/accountability/fraud-expert-pushes-procedures-safeguard-parish-collections

Is there not such a thing as consensus, and the power of prayer to the Holy Spirit to help achieve it?

As Aidan has been arguing it is the facility with which clergy can derive from canon law as it stands an excuse for keeping to themselves control of virtually everything that inclines them to share nothing at all, not even a microphone at a gathering often. That undivided power frustrates dialogue, without which it is difficult now to say what authority the church has left to talk about.

Re regarding priests as of disputable regard, see today’s review of Fr Michael Hurley’s book on ‘Inspiring Faith Communities’. Clericalism is the problem and canon law at present institutionalises that.

My opening remark in the context of the above was: “The Church in a multiplicity of its documents repeatedly urges the meaningful involvement of the laity in the evangelical mission of Church together with the duty of the laity to participate in such.” That’s the principle which grounds my subsequent submissions. I am interested in finding out as accurately as possible what the ACI is saying about this. Allusions to the problems created by purported clericalism abound everywhere but are unclear in their definitions or on the ecclesiology that underpins them. Indeed some authoritarian practitioners are among the strongest overt advocates for lay involvement.

I presented two real life scenarios to seek to understand what the ACI general position is. If there was a significant presence of ACI members in my parish, what approach would I expect them to take? What should happen when “push comes to shove?” One scenario pertained to the exploration of a practical parish exercise or undertaking in terms of lay involvement. This involved a necessary question regarding necessary considerations of both civil and Canon Law. The second focussed on a ministry of a priest of positive reputation who practised involvement of the laity, and what lay involvement would look like in that more spiritual context.

The one direct answer given questioned the feasibility of the renovation of the church building. On the ground it would have involved the PP dealing with two groups of parishioners instead of one. And so on. This introduced a degree of complexity among the laity themselves.

Both scenarios, I believe, offered scope for clarification regarding the ACI stance. It did not emerge.

This website conveys a sense of discontent regarding the question of authority. The last reply seeks my opinion on the issue of sharing of authority. The answer relies on what the notion of sharing authority means in a Catholic parish context. The enquiry I have made here with the two scenarios asks precisely what the ACI believes the actual shape this sharing of authority should take in real life situations. Not what shouldn’t happen but what should. The Association doesn’t need my opinion. If it did so I would, and can, reply. I am the learner here.

My assumption throughout this interaction has been that the contributors here are people who pray and do good works and would be credible sellers of second-hand cars. Lay involvement involves a certain wisdom which relies on the fear of the Lord, which in turn relies on a repentant listening. The negative elements of Church history expounded in this thread draw attention to the dangers of assembling a personal canon on which the self confers authority. The Protestant theologian John Webster speaks of an “inwardness” that asks us to “find” ourselves rather than submitting to a tradition that will shape and mould our thinking. This latter shaped the concept of the ordained priesthood preached by the Cure of Ars. Any treatise on lay involvement must revisit this.

“Lay involvement involves a certain wisdom which relies on the fear of the Lord, which in turn relies on a repentant listening.“

Repentant as in ‘disposed to listen intently to whatever concerns may be raised in objection to whatever he/she the ACI lay person has proposed, and to rethink that in light of those concerns’, OR

Repentant as in ‘regretting the inconvenience he/she is causing to his/her pastor by obliging him to listen to anything’?

I know some diocesan priests who are notable for their fear of the Lord and their disposition to repentant listening, as in definition one above. I know lots more who are not, and who are expectant instead either of deferential assent to their own necessarily wiser decision, or of definition two only from the lay interlocutor.

Remembering that the Cure dArs was distinctly aware of his own struggle to qualify academically for ordination, I strongly suspect that he did not expect deference from those to whom he ministered. Can I take it, therefore, that you are stipulating that pastors too should approach any meeting with a member of ACI in anticipation that on both sides of the dialogue the same willingness to listen and rethink would apply, taking it as read that the lay party would not be assuming the authority to determine the subsequent decisions and actions of the pastor in regard to the subject of discussion?

If that is the case, my own understanding is that ACI does understand collegial dialogue in those same terms. If you are mystified by my own apparent heuristic of suspicion in relation to how ‘repentance’ is understood, and from whom it is expected, you could look at my own account of personal experience in the diocese of Derry since retirement in 1996, at:

http://www.seanoconaill.com/catholic-church-internal-trials-in-the-diocese-of-derry-ireland-in-2019/

My own definition of clericalism would be:

An unspoken contract and understanding that pastor / lay interchange would be simply a benevolence / deference exchange.

The lay person has come to be appreciated for his loyalty and obedience, forever, to whatever the pastor may decide on anything, completely satisfied that even to have been granted this time in the same space has been entirely in itself a bestowal of grace and favour, and therefore sufficient.

And the priest will finish this meeting entirely satisfied that in doing no more than show appreciation for this forelock-touching he has entirely satisfied his pastoral obligation.

It is, in other words, a hangover of the Landlord era, when the ordained priest typically supposed that he had the same entitlement to forelock-touching from his parishioner as the landlord himself. Did you know that many Irish people do indeed refer among them themselves to clericalist diocesan clergy as ‘the last of the landed gentry’?

Thankfully there are many priests who do not suffer from this affliction now, and it cannot long endure. And forelock touching to clergy is almost the equivalent of the flat cap now.

Unfortunately there is still no answer to the two questions regarding two scenarios put earlier. I assume the ACI has practical answers to them. The latest reply again diverts back into questions of theory, argumentation, definitions, – mere debate.

The title “Association of Catholics in Ireland” portrays quite a concept. It might be more accurate to place the word “An” at the front. But that is not important. What is important is that a group of people, whose number I do not know have formed themselves into an association to augment Catholic evangelisation. That such an organisation and structure exists is important. If like any Catholic group it works towards the glory of God, it has the potential to develop a head of steam.

In the Irish Republic decades of reports, theses, papers on educational development gather increasing layers of dust on shelves. They amount to talk but no action. They often contain references from elsewhere supporting some posited theory. In the meantime a number of curriculum centres did an enormous amount of developmental work with schools which mainstreamed into the overall system.

I assume the ACI members gain from interaction with each other; that processes of lighting the proverbial candle occur. But the website does not convey this. Despite some enriched spiritual insights, as stated before what comes across is a sense of discontent. Most of the material predictably and repeatedly pertains to a few issues. A lot of effort risks the same plight as the educational research mentioned above.

The Legion of Mary is one of the great evangelical bodies still a very influential movement in parts of the world. A simple formula of prayer and good works.

A few years back a trio of laity in one parish with the cooperation of the PP funded and led the conversion of a morgue into a beautiful adoration chapel. Shortly afterwards a lady suggested to the PP that the parish “have a mission.” Although the PP baulked at the idea he gave the go-ahead and a committee of laity under the acute leadership of Mr L sprang into the significant challenge of facilitating the missionary team. More recently again led by Mr L a somewhat different group organised and stewarded of the Sacrifice of the Mass for Covid 19. In the last ten days the PP turned down, stating why, a suggestion by one parishioner. He considered he had done his duty with his suggestion and carried on. (In a matter of child abuse of course that would not suffice) In all the activities the voice on the microphone whenever it occurred was that of the PP. It was regarded as an advantage.

This parish has made headway in lay involvement. More effort in a more spiritual vein lies ahead. The underlying condition is one of trust, where the PP, who is more than able to look after himself, knows that the volunteers won’t put him in a difficult position and will respect him while seeking to influence him. There will be no challenge to Church teaching.

There are four reasons for relating this information which does not exhaust all that is going on. Firstly, it establishes the importance of getting started. Waiting for a fair wind is not a good idea. Secondly the status of the ordained priesthood is respected. Thirdly, some people feel frustrated by the PP and indeed resent the style of other laity. Some have decried Canon Law and its perceived weaponisation. They don’t know that Canon Law derives from Church teaching – changes occurred after Vatican II. Pope Francis who endorses lay involvement strongly did not use the opportunity provided by the Amazon Synod to change any aspect of Canon Law which would weaken the teaching pertaining to the governing function of the PP.

Fourthly, it suggests that a group as organised as the ACI get moving. Utilise the personal resources of the association on small initiatives and cultivate, where possible, (it won’t always occur) a relationship with PPs to enable things to happen. I made suggestions in this regard above. Descriptions, warts and all, and reports on such will greatly enhance the website.

Of course the business of the ACI is its own business. May God guide it in its procedures.

Finally perhaps all could pray for the intentions of a particular priest. He arrived home from Ecuador a few years back after 40 years there. He was well known for building schools and creating a catechetics system wherein parents taught catechism to their children. A strong man! Skilled in lay involvement! But as he touched down in Dublin Airport he had nothing save the clothes on his back and those in a case. Another priest took him in in Cork. My wife and I who didn’t know him had the privilege of having him in our home for two weeks shortly afterwards. He was in bad health.

On Tuesday 17th he celebrates his 80th birthday. He got his health back over a year ago, returned to Ecuador and is ministering in a wilderness where no priest has served before. A great way to cure distress.

Thank you, Neil, for your good wishes and the confidence you show in Our Father’s care of us. That octogenarian’s robust faith is striking. I have met such men in Dalgan Park, returned Columbans – and been impressed by the same ‘lightness’ and resilience.

We have had very different personal experiences of the clerical church, and so our priorities and questions will differ. Our faith in the one who was rejected by the Religious establishment of his own time has to do, I think with the striking accuracy of his criticisms of that system in pinpointing the faults of a clerical system of our own time that sacrificed children to preserve everyone’s good opinion of it.

And since that faith has come to us where we are, not at all sure that the house whose possible requirements of us in the future are as vital as our questions as to its ability to protect children even now, we will get around to your questions when we are sure the building is safe.

Just now other possibilities for the future suggest themselves. As Our Father arranged things so that it was secular agencies that exposed the weakness of the clerical system you prioritise, and under whose continuing protection we feel safe as we are, the questions you ask may never arise for us as an immediate concern. When the lost sheep have been found by the Lord in the desert, that desert becomes for us the safer place to stay than the place where you are, content within the church system that you suppose to be eternal and necessary and we see as possibly passing away.

As in Dublin parents are proving more effective in preparing children for sacraments than schools that do not nurture faith, it will be those parents’ questions that will lead the church and show us all its future. What a pity that wasn’t the case in 1968.

The content of the last reply can’t be true! There, in the midst of the verbiage, the personal projections and the comparisons is a statement that presents the ACI along with its resources embracing an option which reduces it to the realm of the critic of those performing in the arena rather than taking its place in the arena itself.

Last night (Nov 16th) BBC 4 presented what was in effect a documentary of the response of the Paris fire authorities to the fire in Notre Dame. A moment arrived when they decided to “save” one part of the roof and cede the rest to the fire – the enemy, in their terms,. But it emerged that there was a new fire inside the top of one of the façade towers. It contained bells of enormous weight which were supported by a timber structure. Should the timber be burned the bells would fall and bring down the tower. This would knock the second tower, followed by the walls, consigning Notre Dame to a heap of rubble.

The only solution was to send firemen up inside the tower to stem the blaze which was already scorching the timbers. The estimated time available was 30 minutes. The building was dangerous. Should the bells fall their lives were …. The attitude of the fire crew was: fire is the enemy; never shirk battle with the enemy. With a moral nod from President Macron standing beside him, the Fire General approved of the plan. It worked.

The firemen worked with an awareness of an enemy. Catholicism is a constant battle with its main enemy, Satan. I won’t patronise anyone with the implied inferences here regarding the arena.

I am at present banned from the blog of a priests’ association on foot of robust criticism of the behaviour (not the theology) of some of its members. I repeated the criticism to the leaders on two further occasions. A clerical caste system characterised by group speak is at odds with the nature of the ordained priesthood. I dislike the know-all priest but would work with him. The recent Carrick report is useful in places but significantly deficient in comparison with the Murphy Report, even given the latter’s flaws. But neither are the laity much good at dealing with child abuse as it occurs in their own ranks. Clericalism is sometimes in the eye of the beholder.

The ordained priesthood instituted by Christ with its threefold ministry of preaching, sanctifying and governing is a sine qua non for the intentions of The Father. So is the role of the laity extending into the secular world. The two are necessarily complementary but limited in their exchangeability. The interaction between both and their emergent relationships are best developed with trial and error, possibly painful, possibly awkward, possibly frustrated. But there is loads of varied work to be done.

A lot of tolerance has been extended to me here. Thank you.

“ The ordained priesthood instituted by Christ with its threefold ministry of preaching, sanctifying and governing is a sine qua non for the intentions of The Father.”

Can you cite the appropriate scriptural passage(s) here, please?

As I have long sought evidence for the differentiation you insist on here, I shall be delighted to receive it.

Sean, if you read Vatican II document on the subject and subsequent documents and perhaps the Sarah Benedict recent book, you will find material better than I can produce.

Come to think of it, neither you nor I are mentioned in the Bible. Surely a significant omission!

To be honest, as a non member, I feel you have already been too generous in the scope you have given me.

Secondly, I feel it’s better for the members to go to the primary sources, scripture and tradition. Otherwise we can just end up in a dialectic starting from different bases.

Thirdly, I have to attend to other things now.